“Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get to the real meaning of things.”

—Georgia O’Keeffe

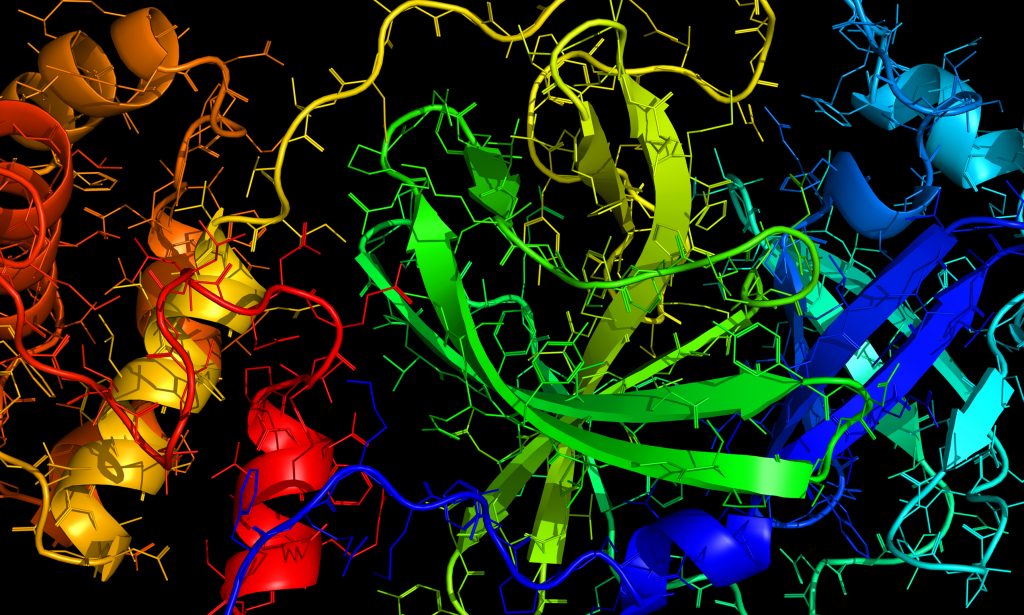

Our collective corona-induced desire to see into the future—from infection and mortality rates, to unemployment, trade, and growth rates—has brought renewed prominence to models, especially epidemiological ones. Many pandemic news stories have invoked George Box’s quip that “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” A model is nothing more than a simplified representation of reality that is often expressed in some formalized way, such as mathematically.

What does it mean for a model to be useful? Usefulness is evaluated relative to the purpose at hand. In this sense, models are like maps or fables. You would no sooner use a subway map to drive into the city than use a street map to ride the subway. Similarly, if a child tells a lie, we recount the story of The Boy Who Cried Wolf, not the story of the Tortoise and the Hare.

Insights from many models are the surest foundation for policy development.

This epidemic has brought debates about the use and misuse of models into the public square. Writing in the Boston Globe, Aubrey Clayton describes one prominent misuse of models by a White House team. Under the standard operating procedure, models are rooted in science and scrutinized publicly. Useful models can then be used to inform the policymaking process. The administration flipped this script. It had been arguing that the virus was under control, and then set out to find a model that delivered this forecast. They disseminated the so-called “cubic model.” They liked it because it was predicting no US deaths by mid-May. Soon enough, the evidence rolled in to show that deaths were around 1,500 per day at that time. The good news out of this episode is that the misuse was revealed.

Advantages of multiple models

Indeed, we are in the midst of vigorous and transparent public debates about the proper and innovative uses for models. Writing in the Washington Post, Scott Page introduces an idea that is by now well established among experts: The insights from many models are the surest foundation for policy development because different models capture different dimensions of our complex reality. The winner of the $1 million Netflix Prize, a multi-year competition to write the best algorithm for predicting user movie ratings, went to a last-minute submission that included the combined contributions of many earlier submissions, including relatively poor performers. As Wired tells it, “The secret sauce . . . was collaboration between diverse ideas.” The same principle is being used in these pandemic days: biostatistician Nicholas Reich began drawing attention when he unveiled his “ensemble model” to make COVID-19 projections.

Why have models proven to be so remarkably salient in the public eye? With models, we can reason about the possible consequences of our actions, and make predictions about the future. The public health campaign to “flatten the curve” was powerful because it helped us “see” the connection between our social behaviors in March and the aggregate rates of infection and death in April.

For example, Harry Stevens published a visually elegant simulation in the Washington Post. It displays the movement of individuals through the world under different restrictions, and then plots the curve for each. It shows us that quarantines alone fail to flatten the curve because they are completely undermined by even small leaks. By contrast, physical distancing has a strong effect.

Models aren’t the only way to see. We also need art and story.

The underlying epidemiological model—the so-called SIR model (susceptible-infected-recovered)—has been around and widely taught in classrooms for decades. One of the innovations of the spring was to superimpose a simple horizontal line labeled “healthcare system capacity” over the infection curve. Simple, elegant, and compelling. We need models to see clearly.

Other ways to see

But models aren’t the only way to see. We also need art and story. Picasso delivered a companion to Box’s quip: “Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth . . .” The truth of a healthcare system pushed beyond its capacity was made comprehensible by images and stories from China, Italy, and New York City, where the prevalence of COVID-19 was high. Art and story also help us deal with these difficult days of isolation and hardship. Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary and the anonymously posted COVID Jesus direct our gaze to courage, sacrifice, solidarity, perseverance, and gratitude. Seeing with models exists alongside other ways of seeing. The arts. Literacy. Numeracy. Models.

As we move through the world in these difficult and confusing times, we lean into these enduring forms of representation to make meaning out of our experiences. But if models and the creative arts are to be evaluated against standards of utility and truth, how do we identify those?

Vibrant communities root themselves in values. Values are yet another way that we can distill meaning from a confusing and messy reality. Values help us see through the cloud of distraction and find our true North.

On integral human development

For the Keough School, the Church’s proclamation of integral human development is an assertion of the core values proper to the ordering of social and economic systems, and to the work of scholarly, policy, and practitioner communities. The Latin root of integral is “integer,” which means wholeness or completeness. When used as an adjective, it implies that the thing it qualifies—here, human development—is indivisible.

As for “human,” it functions as either a singular or collective noun. First, the development of an individual human being arises when the person flourishes in mind, body, and spirit. To reduce a human being to homo economicus, or any other single dimension of well-being, is not adequate to a development initiative that is truly “integral.” Second, the development of a human community will include all members of the community, with particular care for the most vulnerable. To exclude any member of the collective diminishes the whole development initiative.

As a matter of values, integral human development sits comfortably within Pope Francis’ conceptualization of an “integral ecology,” whereby the human being is recognized as a part of the larger natural order. This reflects the conviction, shared by many theists, that the human being and all of creation is a single, indivisible act of God’s creative love.

The global pandemic is an opportunity to see the world in new ways. To see clearly, we bring together our rich repertoire of models, creative arts, and values. In the face of global suffering, solitude, and death, we “see the poor.” In the face of scarcity, we see the fragility of our systems of provision of food, medical supplies, and other essential goods. In the clear skies over New Delhi and New York, we see the beauty of a world without the devastation of humanity’s pollution. Upon seeing clearly, we can get to the real meaning of things.

Tom Mustillo is an associate professor of politics in the Keough School of Global Affairs. His research examines political representation and party competition. He also directs Notre Dame’s minor in data science.

This article is part of a series of blog posts published by the Keough School of Global Affairs. Dignity and Development provides in-depth analysis of global challenges through the lens of integral human development.

Photo: Christian C. Gruber and Georg Steinkellner, https://figshare.com/articles/Comparative_model_of_novel_coronavirus_2019-nCoV_protease_Mpro/11752752