Integral human development, which stands at the center of the Keough School’s mission, affirms that the dignity of the human person is not only expressed in work and economic activity, but also in “cultural richness, artistic creativity, religious belonging, and spiritual practice.” This expansive definition opens up methodological possibilities in which religious creativity and the desire for God become integrative sites for human development. The project “Art, Desire, and God: Phenomenological Perspectives,” on which I have been collaborating with my research students, explores these possibilities. We are asking anew the ancient question: How is human desire for God, as expressed in the experience of beauty, constitutive of our humanity and capable of integrating relationships and communities?

Beauty and the burning of Notre-Dame

The urgency of this question emerged following the tragic April 2019 burning of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. This event made manifest the multiple identities engaged by aesthetic experience in our contemporary world. Immediately after the fire, both secular humanistic and religious discourses were deployed in articulating the importance of the restoration and preservation of the building. Notre-Dame de Paris was simultaneously cast as a historical and cultural symbol of the French Republic, a religious monument of both Roman Catholicism and global Christianity and a work of artistic genius displaying the depths of humanity.

Standing in front of the burning cathedral, Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris claimed, “This place leaves no one untouched—when you enter this cathedral it inhabits you.” The challenge of Notre-Dame is precisely to understand why the crisis surrounding it left no person untouched.

Violence and fire have forced a return to creative, integrative questions about desire for God.

Since the fire, for example, scholars across disciplines have looked to the physical building of the cathedral to pose these human questions. Using but the single example of the stones of Notre-Dame: labor historians speak of the stones as the embodiment of builders wielding chisels and working for something they might have never seen completed; museum presidents have described the stones as memories built into monument made of flesh and history; and the Archbishop of Paris described the same as the site of a “trial” of faith and meaning. Stones dedicated to God have become the intersectional site for reflection upon human persons and human relations.

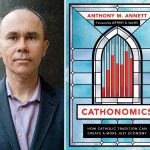

The artist Stephen Barany, a University of Notre Dame graduate in theology and design, helped us to pose the question of how the cathedral serves as a mirror for understanding the human person in relation to God. Barany produced the image displayed here.The darkened shadow of Notre-Dame de Paris glows with the haunting hues of a fire still burning. The spire is gone; the smoke filters and reflects the light. Yet, the hint of scaffolding over the nave and the matrix-like background of this contemporary take on the Gothic edifice suggest that a rebuilding will happen. Violence and fire will have forced a return to creative, integrative questions about desire for God.

While the rebuilding efforts for a high medieval building in Western Europe might seem far from some notions of development, integral human development sees a different opportunity in the rebuilding initiative, not only for Parisians but also for the rest of the world.

Considering phenomenology

In breaking open the inner significance of the cathedral crisis, phenomenology is uniquely relevant. By phenomenology, we mean the study of the appearance and meaning of things as they occur in human experience. This philosophical movement gained ground with thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and others in the early twentieth century. Initially, phenomenology avoided theology and theological questions. However, thinkers like Ricoeur, Marion, and Levinas are credited in the second half of the twentieth century with a “theological turn,” after which phenomenology begun plumbing the depths of human expressions of both the desire for God, broadly construed, and the desire for God expressed aesthetically. It is precisely phenomenology’s ability to dive into these particulars—resisting generalization—that renders it so philosophically and theologically potent.

In The Unforgettable and the Unhoped for Jean-Louis Chrétien, one of the prominent phenomenologists of our age, writes: “Religious and mystical thought and speech are necessary for those who would meditate on excess and superabundance, on the force in weakness and the perfection in deficiency. They do more than speak of them; they live them and originate from them.” Phenomenology pays systematic attention to the overwhelming nature of an experience like the burning of Notre-Dame. While Chrétien makes the case for this attention in texts and speech, an equally powerful case is to be made for film, sculpture, painting, music, and sacred architecture. Chrétien, and phenomenology generally, allow us to approach religious texts, traditions, buildings, and expressions of beauty as performative traditions in which human persons, live, move, and have their being.

Given the multiple actors invested in Notre-Dame de Paris, the site becomes itself a question for how desire for God expressed aesthetically directly opens onto questions of human relation and aspiration. For example, with Notre-Dame smoldering, Paris Archbishop Michel Aupetit preached in a Holy Week homily that the cathedral “is on its knees.” He personified the building in such a way as to describe not only the material state of the edifice, but also the way in which it performed an act of humility shared not only by the Passiontide pilgrims of that fateful April burning, but also of a city, and a culture. The kneeling cathedral encoded the humble desire for God as the foundation stone of the new building in which many actors—Catholic and not—would participate.

The burning of Notre-Dame de Paris has provided an opportunity to reflect on human persons’ desire for God, and how such desires are manifested in appreciation of beauty.

The Notre-Dame Cathedral burning has inspired growing discussion about the arts and desire for God at the University of Notre Dame. In an October 2020 global, virtual conference hosted by the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame, scholars applied phenomenological methods to aesthetics and desire for God from diverse angles. The result of these investigations produced three phenomenological categories—embodied experience, carnal encounter, and incarnate performance. In the research that produced the first, scholars probed the manner in which art and film express embodied desire for God. The second, carnal encounter, emerged from exploring the limits of the mystical in desire for God. And the final category, incarnate performance, focused on expression through race, gender, and liturgy. These three categories, though only emergent, address the heart of integral human development’s “cultural richness, artistic creativity, religious belonging, and spiritual practice” and will hopefully be developed for broader use. For now, it is important to recognize their emergence from a kneeling cathedral.

The partial burning of one of the world’s most famous cathedrals has provided an opportunity to renew the love of learning how it is that human persons desire God, and how such desires are incarnated aesthetically. The world’s diversity of cultures, religious practices, and approaches to (or denials of) the divine only re-inscribe this question, which lies at the integrative center of human life. At stake is more than how Notre-Dame de Paris will be rebuilt. The heart of the matter is the desire for that which is beyond the self—for God, a desire which continues to shape shared aesthetic expressions of our humanity. It is a bracingly big question, one which “integral human development” both allows and demands.

Kevin G. Grove, C.S.C. is a systematic theologian who works on issues of memory and desire in sacramental, fundamental, and philosophical theology. He holds a PhD in philosophical theology from the University of Cambridge (Trinity College) and has been a member of the Notre Dame theology faculty since 2016. He is a faculty fellow of the Keough School’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies.

This article is part of a series of blog posts published by the Keough School of Global Affairs. Dignity and Development provides in-depth analysis of global challenges through the lens of integral human development.

Cover artwork by Stephen Barany