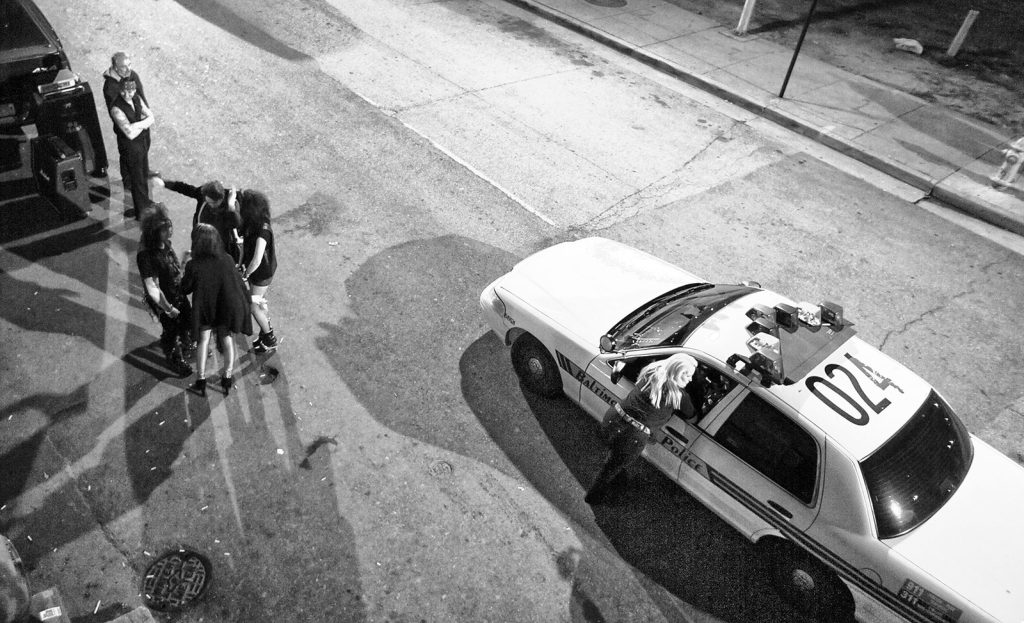

Human beings experience hundreds of events and encounters on a weekly basis, but only a precious few of them leave a lasting impression on us. I experienced one of those rare moments on April 29, 2015 in the city of Baltimore–a day in which the city was both figuratively and literally burning.

Baltimore’s troubles did not begin in April 2015; a chronic state of tension had long existed between the predominantly Black neighborhoods of the city and the institutions meant to serve them. Yet the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, caused by trauma suffered while in police custody on April 19, was a spark that lit the flame.

What began as largely peaceful protests in response to the wholly unnecessary death was replaced by violence, looting, rioting, and overall chaos as frustrations over perceived and actual inertia, inaction, and injustice boiled over. It felt very much as though months, weeks, years, decades, and generations of frustrations over dehumanization and assaults to dignity were finally coming to a head. By the end of April, the city was on virtual lockdown as sporadic violence and looting continued, and authorities from the city, county, state, and beyond began to lower the hammer to tamp down the violence. An air of deep unease and uncertainty about what had just happened and why it had happened pervaded the city.

Which brings us back to April 29. As fate would have it, that week my employer at the time, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), was holding a global summit on agricultural livelihoods that included staff from around the world. As the situation in the city deteriorated, these staff were holed up in a hotel downtown, anxious that the violence should reach them. A decision was made to proceed with some of the summit sessions as planned. Scheduled to facilitate a session at the summit, I made my way downtown with trepidation. Evidence of the violence was pervasive, including an ominous haze caused by the smoldering embers as the fires across the city were put out.

The topic of my session was defining and assessing CRS’s overall organizational effectiveness around programs to place agricultural households on a “pathway to prosperity” that reflected their specific circumstances. I listened with great interest to the global perspectives set forth—running the gamut from wholly pragmatic, easy-to-measure “quick wins” to mission-centric and idealistic benchmarks.

After the session, I needed to make my way back to my office nearby for a separate meeting, but none of the taxi or rideshare services were operating. This meant, much to my dismay, making the trek on foot through some of the violence-affected areas. As I was thus proceeding—head down, hands in my pockets, at a brisker than usual pace—I was approached frantically by a young lady asking me if I had a phone and to follow her, as someone had collapsed in the street. She took me to a man in his mid-twenties lying unconscious on the sidewalk. He had slipped underneath the bench at the bus stop in front of a shop that had been looted and subsequently boarded up in the previous two days.

I called 911 on my cell phone, and much to my surprise, the call was answered right away; I had suspected that the line would be busy given the chaos all over the city. The emergency responder on the line walked me through some steps to check vital signs and get a sense of what might have been wrong. Then she had me count out his breaths, which were alarmingly slow. I kept trying to talk to the man, but he was completely unresponsive. She kept me on the line while we waited for the paramedics, who showed up about ten minutes later in a full-sized fire ladder truck.

I will never forget the interaction that followed. Just as the emergency vehicle pulled up, sirens blaring, the man moved his head and began crying—the first real sign of life that I had seen from him. Three emergency responders jumped out of the ladder truck; I sensed from the looks on their faces that they were silently judging the man. Rather than tend to the man on the ground, they turned to the bystanders and the man’s companions to ask what drugs they were high on and what had happened; their tone was sneering and mocking.

When they turned their attention to the man, they did not actually attend to him; rather, one of the responders dragged him by his shoes along the sidewalk to the curb by the ladder truck; I recall vividly the sickening sound of body and head scraping against pavement. The responders treated me cordially, but they also seemed annoyed that I had wasted their time by calling emergency services. They didn’t talk to me or any of the others while they waited around for an ambulance to arrive.

Uncomfortable questions

The episode left a sour taste in my mouth, though I tried to give the first responders the benefit of the doubt, recognizing how demoralizing and stressful the days of rioting and destruction must have been for them. I might have behaved in the exact same way if I was in their circumstances at that place and at that time. However, as I watched how they treated the citizens, I could not help but think that kind of attitude and behavior from the supposed protectors of the city was precisely why Baltimore was burning. This experience raises a number of important questions that I continue to pose to myself and through my work and my research.

Does respect for our human dignity depend on our behavior or other personal characteristics?

If the roles had been reversed and I had been the unconscious man—a White, middle- class, working professional—I almost certainly would have been treated differently in that circumstance. I would have been outraged if I had found out that the first responders not only didn’t attend to me right away, but then dragged me around the ground like a rag doll. Is it because I am somehow more worthy of having my humanity and dignity recognized than a man who seemed to the naked eye to be homeless and intoxicated? Do persons who are or have engaged in violent or other harmful and criminal behaviors deserve less recognition of their humanity than those who don’t? In other words, is our humanity something that is earned? If one undertakes actions that society deems criminal, undesirable, counter-cultural, or anti-social, is respect for that person’s dignity forfeit?

A biased evaluation of dignity threatens to imprison entire groups of people in a cycle of dehumanization and disrespect

Answering yes to these types of questions leads to a slippery slope: who gets to determine if a certain behavior makes one worthy or unworthy of having their basic humanity recognized? A society that believes that respect for dignity is a meritocracy is at deep risk of ensuring that any sort of minority population becomes less worthy of dignity than the majority. Indeed, our implicit biases likely have a strong impact on who we treat with respect and whom we deem unworthy of this respect. This bias-driven evaluation of dignity threatens to imprison entire groups of people in a cycle of dehumanization and disrespect for generations. This slippery slope has led to catastrophic abuses of human rights up to and including genocide. This idea also flies in the face of the 1948 “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” which centers on the conviction that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” The idea of “equal dignity” was further embraced by Pope Paul VI in his encyclical Populorum Progressio.

How do we balance a universal respect for dignity with individual accountability?

Rejecting a merit-based view of dignity poses the important question of how we adopt a universally dignity-affirming lens without absolving individuals and groups that are engaging in harmful and oppressive behavior. An argument could be made that the man in distress wasn’t actively harming or posing the threat of harm to anyone involved, and should therefore be granted the same treatment as any other, but this raises other questions about his life choices. How much responsibility do individuals have to become what Donna Hicks refers to as “agents of dignity”, and what happens if they fail to do so? Does the system respond in kind? When an individual’s behavior is a nuisance, antisocial, or outright harmful to others, how do we appropriately condemn that behavior while also preserving that person’s humanity? These are thorny questions, but I believe that it is only in grappling with these difficult questions that we can hope to move towards a more humane society.

Did these first responders perform their duties? The answer to this question depends on perspective. No doubt my reflections around this incident were colored by the conversation with CRS colleagues that I was engaged in immediately prior: how we define and measure the success of interventions and organizations. In general, a first responder’s job performance is judged by speediness of the response, keeping a cool head under pressure, and linking those in crisis to urgent care before the crisis claims that person’s life. By those benchmarks, the encounter could easily be considered a successful one. They responded quite speedily, they came prepared for all manner of eventualities, and they transported a person in distress to a health care facility that could address the health crisis that this person was facing. Mission accomplished.

At a more qualitative level, however, this was not a successful encounter. Indeed, the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, for instance, has a code of ethics and an accompanying EMT oath, the second tenet of which is a pledge “to provide services based on human need, with compassion and respect for human dignity, unrestricted by consideration of nationality, race, creed, color, or status; to not judge the merits of the patient’s request for service, nor allow the patient’s socioeconomic status to influence our demeanor or the care that we provide.” Through the lens of this oath, the encounter was flawed.

This again raises additional questions: Should we be holding ourselves and our institutions more accountable for respecting the dignity of human persons? Would doing so undermine the other goals of an organization if staff become so afraid of causing offense? How would adding a dimension of dignity affirmation to institutional and programmatic definitions and metrics of success change the way our society operates?

What I am posing goes well beyond simply giving the nicest people in an organization a pat on the back. It is about how institutions fundamentally perceive individuals. It is more about imagining a world wherein alongside professional excellence, we also recognize interpersonal excellence. In addition to technical abilities, we reward approaches, behaviors and institutions that affirm the equal human dignity of all alongside their work.

In the words of Tavis Smiley in response to the chaos in Baltimore, “these riots aren’t a Black or White thing—they’re a humanity thing, a dignity thing.” Smiley went on to say that unless we understand this and have the courage to change our institutions, that “protests and riots–uprisings–could become the new normal.” I will take this a step further and state that any institution, policy, practice, project, or organizational culture that actively or passively, explicitly or implicitly dehumanizes, shames, or strips of a sense of dignity any of the citizens it was established to serve should be re-examined, no matter the objective outcome it was established to achieve. We should no longer enable these types of institutional cultures in our midst if we are ever to ensure a more just and equitable world.

At the moment, we have more questions than answers in this space, but I believe we need to be asking those questions more forcefully as the social fabric becomes more and more strained. In the years since the Baltimore riots, we continue to be mired in an epidemic of racially charged violence perpetuated by public servants upon the citizenry, up to and including the latest episode–the beating to death of Tyre Nichols. If we do not hold our civil service and other social institutions accountable in different ways, then the epidemic of violence and dehumanization will continue unabated. The cost of inaction and maintaining the status quo in lives, prosperity, and peace is too high.

Paul Perrin is Director of Evidence and Learning, Pulte Institute for Global Development and Associate Professor of the Practice, in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.

This article is part of a series of blog posts published by the Keough School of Global Affairs. Dignity and Development provides in-depth analysis of global challenges through the lens of integral human development.

Photo: “Baltimore riot” by Ted Van Pelt is licensed under CC BY 2.0.