Carlos Lozada is quick to assert he’s no policy wonk, nor a political scientist or politician. But as the nonfiction book critic for the Washington Post, a newspaper that focuses on national politics and the federal government, he is well-versed in these worlds.

“I spend my time reading the books these people write and passing judgment on their ideas,” said Lozada during a recent visit to the Keough School of Global Affairs.

Speaking to master of global affairs and undergraduate students, Lozada reflected on the role of political books published during President Donald Trump’s administration.

“Books have become an essential way not just to chronicle and interpret the Trump era, but also to litigate its battles,” Lozada said. America’s intellectual class, he added, has responded to Trump’s policies with an onslaught of books.

“It’s ironic that a man who says he has no time to read has basically launched a nationwide book club.”

Lozada summarized publishing trends he has observed over the past three years. As Trump began winning Republican presidential primaries in 2016, for example, the condition of America’s white working class became the subject of intense cultural debate. This interest gave rise to national bestsellers such as J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy.

After Trump won the presidential election, dystopian novels such as George Orwell’s 1984 topped bestseller lists. Then came the “resistance literature,” written by Trump critics on both the political right and left.

“While writers on the left are waging war against Trump, on the right they are waging a civil war for the conservative movement,” Lozada said.

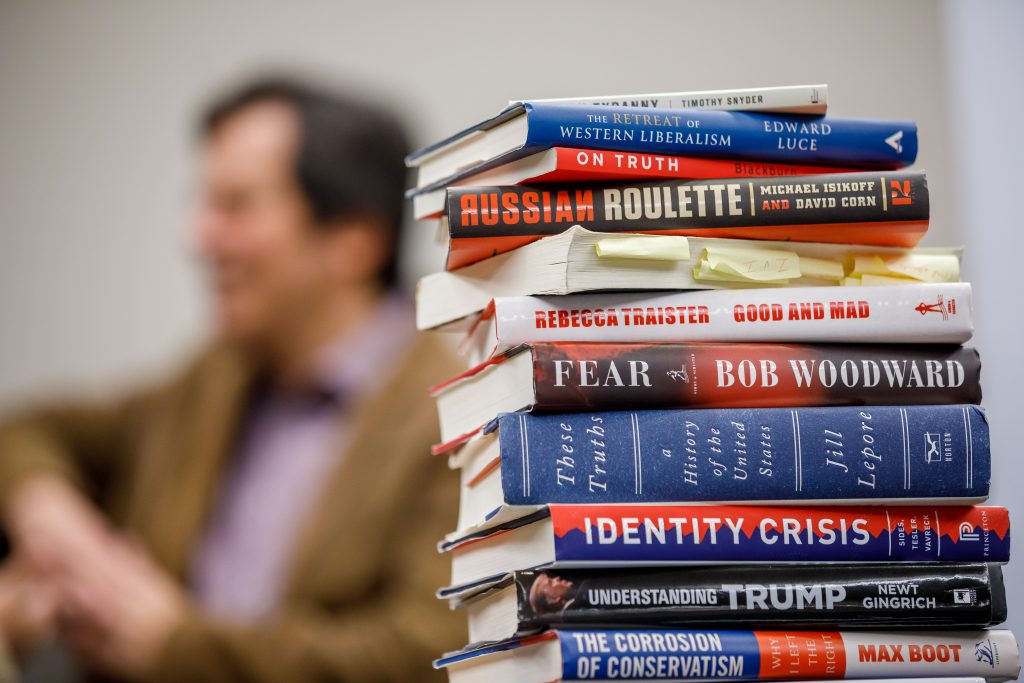

While ideological battles raged across pages, day-to-day accounts of the Trump administration emerged, such as Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury. Other books chronicled Russian interference in the 2016 election, such as Russian Roulette by David Corn and Michael Isikoff and Cyberwar by Kathleen Hall Jamieson.

“Some of these books are terrific, but they also feel like a Google doc you’re constantly updating,” Lozada said.

Meanwhile in the academy, a group of books Lozada describes as the “Death of” books arrived on the scene.

“Political scientists warn of the death of democracy; philosophers worry about the death of truth; presidential historians see the death of leadership; economists and finance writers lament the destruction of Western alliances and international agreements,” he said.

Lozada quoted Financial Times columnist Edward Luce, author of The Retreat of Western Liberalism, who wrote: “Trump has made clear the post-war U.S.-led global order is history. But what will replace it?”

“This is really the crux of everything, where Trump challenges the intellectual class and you all as well,” Lozada said. “What Trump is really doing, in a chaotic way, is that he forces us to question first principles: what this country is all about and what its role in the world should be. What is the proper immigration policy for the United States? What is NATO for in the 21st century? What is the right trade policy in an era when deep and worsening inequality is a fact of life? Trump forces a rethinking of all this.”

This led Lozada to share one final observation:

“Some of the books I’m most excited about are those that help us look at this big picture of what America stands for, at home and in the world.” He cited one example as the newly published These Truths, by historian Jill Lepore, which examines equality, natural rights, and popular sovereignty, examining how U.S. has upheld them over the course of history.

“This book is only very passingly about Trump, yet it gets to the heart of the debates we’re having in the Trump era. The best books of the Trump era are not really about Trump at all.”

A Notre Dame graduate who majored in economics and political science, Lozada was a 2018 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. Before becoming the nonfiction book critic at the Post, he served as the newspaper’s economics editor and national security editor. He also is the former managing editor of Foreign Policy.