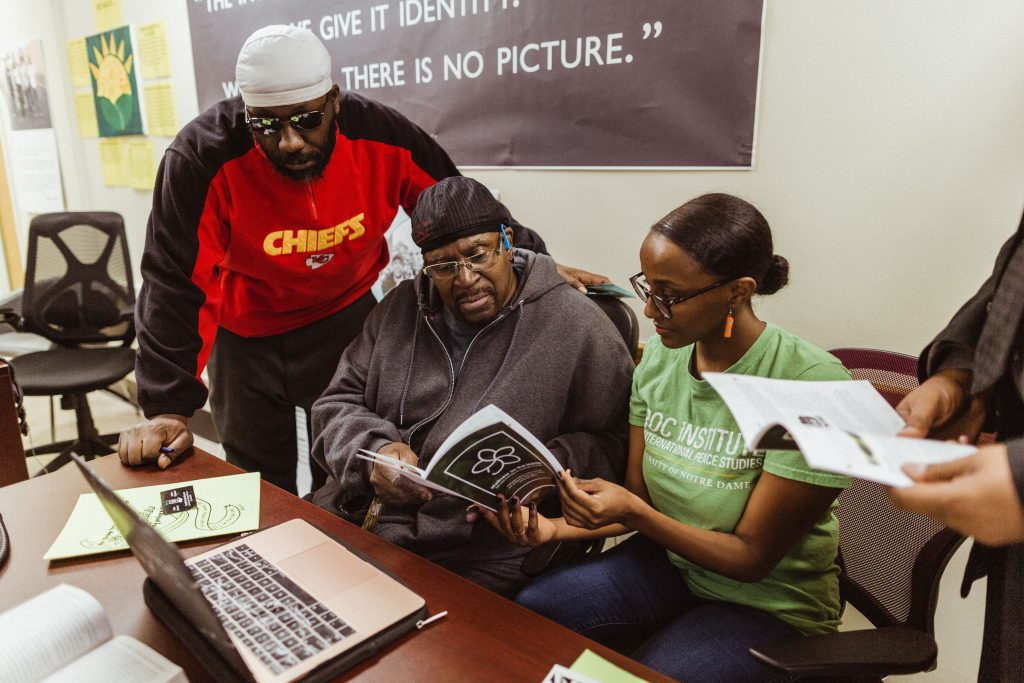

Photo, left to right: Leonardo Wiley, Anthony Holmes, and master of global affairs student Helina Haile examine “Wellness on the Inside: Tips and Activities to Care for Yourself,” the Chicago Torture Justice Center’s new guide for incarcerated survivors of police violence. Wiley and Holmes are both survivors.

When searching for an internship organization during her second year of studies at the University of Notre Dame, Helina Haile knew that she wanted to work alongside an organization focused on systemic racism in the United States. Her search led her to the Chicago Torture Justice Center (CTJC), a first-of-its-kind organization dedicated to supporting survivors of police violence.

“After my first year at Notre Dame, I really wanted to change the perception that the West, and especially the US, is the giver of peace and other countries are recipients,” said Haile, who is completing her second year as a master of global affairs student at the Keough School of Global Affairs.

Grassroots movements and organizations are creating theories that are as important as theories developed in academic institutions.

During their second year of global affairs coursework, most international peace studies students work for six months with an organization that focuses on peace and justice issues. While Haile was searching for an organization, David Anderson Hooker, associate professor of the practice of conflict transformation and peacebuilding at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and vice chair of CTJC’s board, asked Haile if she would be interested in working at CTJC, engaging the development and evolution of its “politicized healing model.”

“To look at peace, justice, trauma, and community in our own backyard—less than 100 miles away from Notre Dame—was a really excellent opportunity,” said Hooker. “And because CTJC is engaging an emerging set of ideas, it wasn’t just that the center would be good for Helina, but she would be good for the center, too. She could join in the conversation about how to articulate politicized healing.”

Photo, left to right: Master of global affairs student Helina Haile with Ariel Atkins of Black Lives Matter Chicago and Chicago Torture Justice Center co-executive directors Aislinn Pulley and Cindy Eigler.

CTJC was established as a result of the 2015 Reparations Ordinance passed by Chicago’s City Council. It was created to address the impact of racially motivated police torture during former Chicago Police Department Commander Jon Burge’s tenure (1972 to 1991). The ordinance came after three decades of activism led by survivors, their family members, and allies across Chicago.

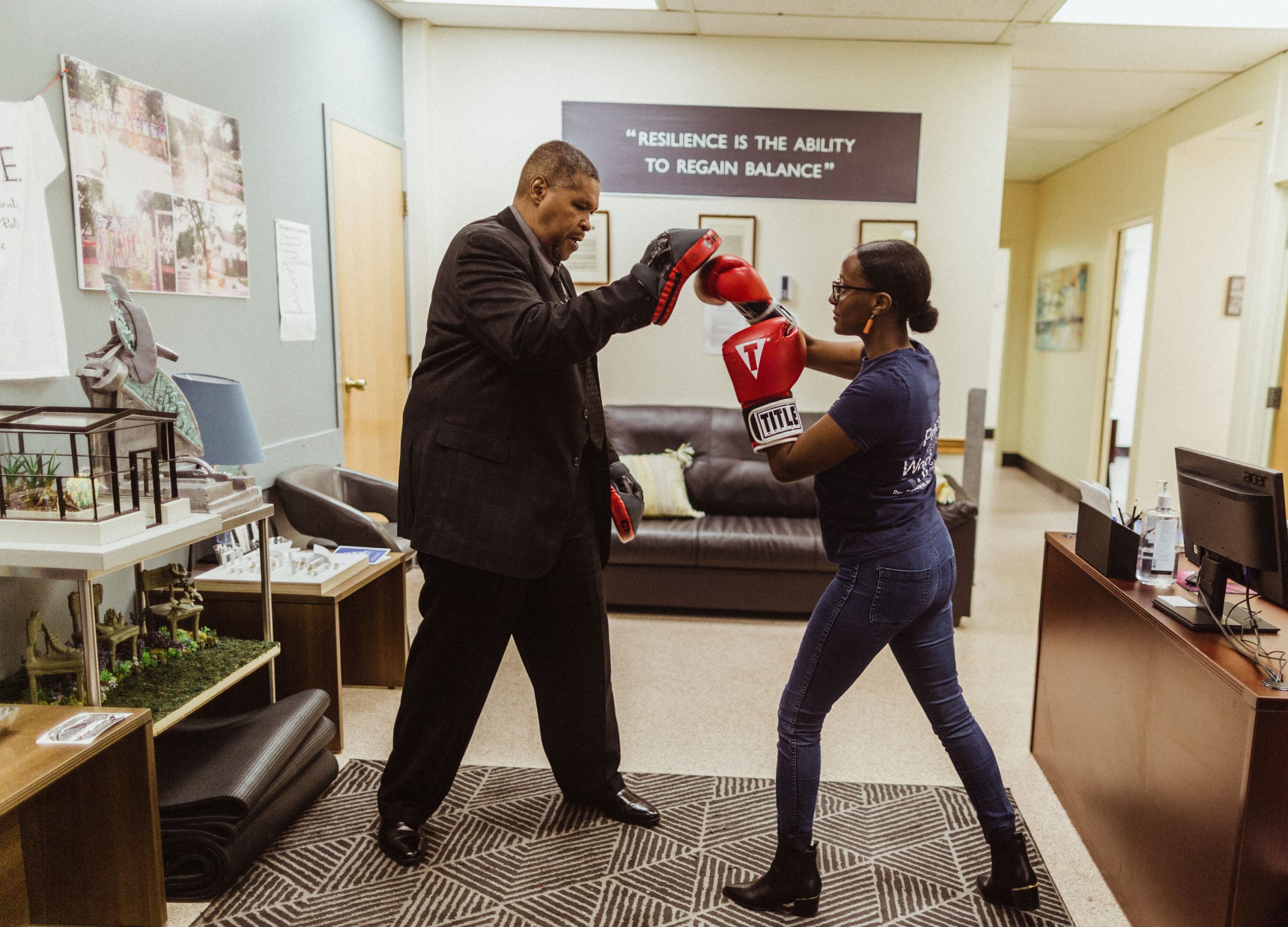

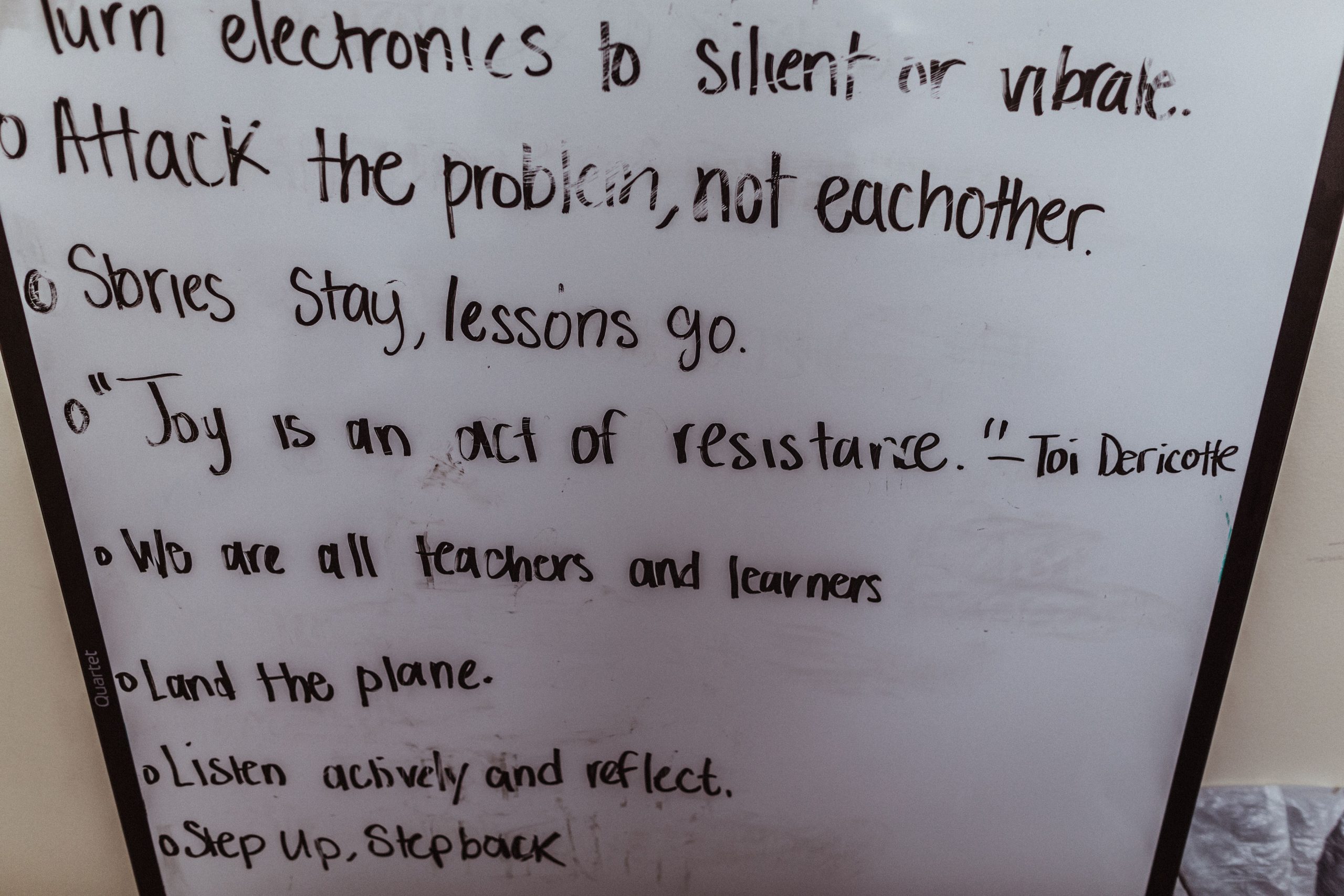

To fulfill this mandate, CTJC leaders developed the politicized healing model which includes three focus areas: healing from trauma through traditional and non-traditional approaches including counseling, support groups, music, acupuncture, and boxing; working to dismantle systems that perpetuate racial violence; and developing new frameworks for community justice and accountability.

We need to look at what’s happening to Brown and Black people in the United States as acts of terror.

“There’s so much talk about reparations on a national scale, but it’s being used in really limited ways,” said Cindy Eigler, co-executive director at CTJC and Haile’s supervisor during her time at the Center. “If you look at just financial and material redress, you’re really disappearing so much of the emotional, physical, and spiritual harm that needs to be addressed. In everything we do, we want to promote a more honest and holistic conversation that can get to real repair.”

After Hooker’s invitation, Haile was excited to learn more about this cutting-edge work and contacted staff members about an internship. At CTJC she served as a first point of contact, working to build relationships with survivors and fielding questions from journalists and others interested in the Center. Haile’s daily activities also included helping to build an archive to document the Center’s work, engaging with a boxing program, providing graphic design services, and pitching in where most needed.

Photo, left to right: Chicago Torture Justice Center Learning Fellow Gregory Banks, a survivor of police violence who now leads the organization’s new boxing program, with MGA student Helina Haile.

“Almost every day I see connections here to the wisdom of people of color we read in class, like Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality and Paolo Freire’s pedagogy of the oppressed,” says Haile. “Being here has allowed me to break the scholar-practitioner divide and not reinforce it, and I’m looking at ways that I can go back to Notre Dame and emphasize the fact that grassroots movements and organizations are creating theories that are as important as theories talked about in academic institutions.”

Working alongside CTJC staff, Haile had a front row seat to witness the first US municipality commit to providing reparations to those harmed by racially motivated police violence. CTJC takes its trailblazing role seriously. Staff are making resources and publications exploring CTJC’s philosophy available online free of cost and are also seeking new ways to tell their story publicly, too, to support other communities interested in similar efforts.

“The way that state-sponsored violence and targeted exclusion happens in various communities around the country might differ, but if we can fully and effectively articulate how politicized healing works, you can take that idea and apply it in other contexts,” said Hooker. “That’s the most important export.”

Photo: Ground rules for a meeting of RISE (Realizing and Implementing Strategies to End Police Violence), a program of the Chicago Torture Justice Center.

CTJC’s impact and reach continues to expand. In 2019, the Center provided therapeutic services for 193 individuals and reached hundreds more through its speakers bureau, public events, and community programs. But despite the demonstrated need for CTJC’s services, the future remains uncertain. Because the US government does not acknowledge “domestic torture,” CTJC is not yet eligible for federal funding. Funding from Illinois and the city of Chicago remains uncertain—leaving the organization to rely increasingly on private donations and grants.

This struggle to carve out a new space of possibility, as well as CTJC’s wide-ranging reparations work and its focus on ending police violence, served as an encouragement to Haile to expand the frameworks for justice and peacebuilding she encountered in the classroom at Notre Dame.

“This work is a reframing of what we conceptualize as terrorism or torture,” she said. “International peace studies has a tendency to look at these concepts as something that happens ‘over there,’ but we need to also look at what’s happening to Brown and Black people in the United States as acts of terror, too.”

Impact continues after graduation

After graduation, Haile continued to draw on the politicized healing model she learned at CTJC.

During summer 2020, she was selected for a Black to the Future Public Policy Fellowship, part of the Black Futures Lab, an initiative founded by Black Lives Matter Movement co-founder Alicia Garza to work with Black people to build political power with and for Black communities across the US. The six-month long fellowship included training with a cohort of other fellows around the country, with the end goal of building a policy proposal supporting Black communities. Haile’s policy proposal focused on expanding reparations efforts in Chicago and was developed in collaboration with CTJC.

“The politicized healing model has really provided me with the ability to stay grounded in the tensions I was experiencing between peace, justice and healing,” said Haile. “The transformative work of the center is that it transforms you, and equips you to continue to work for liberation.”

Haile will continue to work with the Center to enact the policy proposal she has developed this year, and is also applying to law schools for fall 2021. During her studies, she plans to draw on the politicized healing model, applying it to the intersections of health and law with an abolitionist framework in service of Black communities.

Haile is also engaging with and learning about an emerging focus at the Center, politicized grief.

“In trauma healing processes and in transitions, you have to first grieve whatever loss there has been,” said Hooker. “In the grieving process, we’re inviting survivors into a rhythm of self-reflection and self-care that leads into communal analysis, commitment and activism.”

The politicized grief initiatives invite survivors to participate in four different types of activities including boxing, creating and performing spoken word and poetry, gardening, and building “resistance songbooks” (personalized soundtracks to accompany people on their journeys).

To learn more about the Chicago Torture Justice Center, visit chicagotorturejustice.org/. The Center is also in the midst of a Love-a-thon for Justice, inviting people around the world to support the Center and to spend six weeks engaging in practices around the themes of safety, strength, vision, release, abundance, and satisfaction.

Photography by Ez Powers.

Originally published at kroc.nd.edu on January 24, 2020, and updated on November 30, 2020.