Keough School hosts two Nobel Peace Prize laureates

May 10, 2018 — The Keough School of Global Affairs concluded its inaugural academic year by hosting two Nobel Peace Prize laureates.

Muhammad Yunus, an economist who won the 2006 Nobel prize along with his microfinance enterprise Grameen Bank, delivered the Notre Dame Forum “Going Global” keynote lecture on April 12.

Beatrice Fihn, executive director of the 2017 Nobel prize-winning organization the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), delivered the 24th annual Hesburgh Lecture in Ethics and Public Policy on April 17.

Yunus also met with students in the Master of Global Affairs program and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, while Fihn spoke with undergraduate and doctoral peace studies students from the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

“It is an honor for the Keough School to celebrate the close of our first academic year with visits by two distinguished guests,” said Scott Appleby, Marilyn Keough Dean. “Professor Yunus is a world leader in fighting poverty, while Ms. Fihn is a world leader in building peace. Who better to inspire our students—all of us—than these two champions of integral, ethics-based human development?”

BANKER TO THE POOR

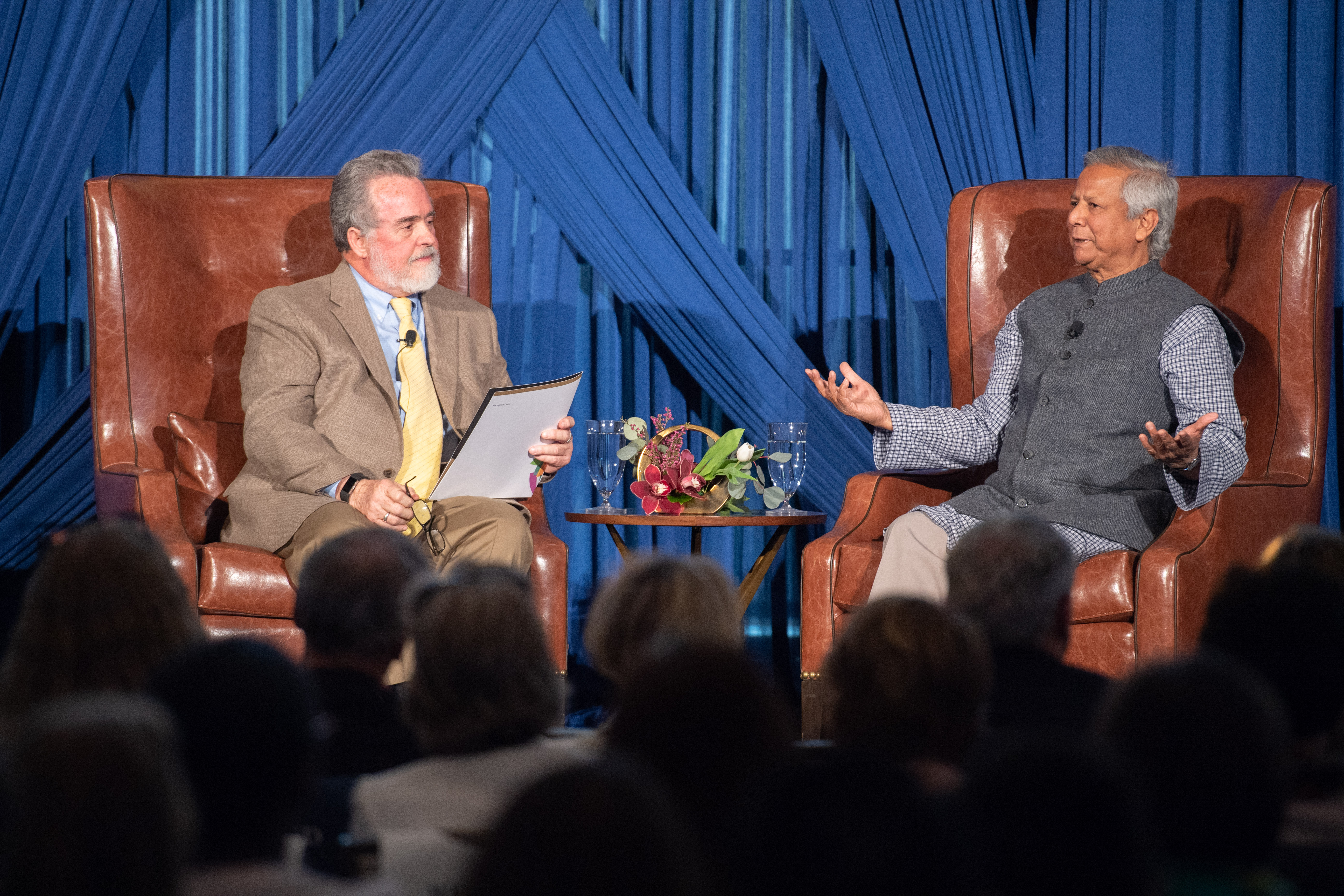

In an onstage conversation with Ray Offenheiser, director of the Notre Dame Initiative for Global Development, Yunus told the familiar story of Grameen Bank to 650 audience members. In the 1970s, as an economics professor at Chittagong University in Bangladesh, Yunus saw people struggling to survive. He was especially discouraged to see loan sharks taking advantage of poor women with no hope of escaping the harsh payback cycle.

“I thought, ‘What good is the economics that I teach?’” Yunus said.

Because poor women were not considered for bank loans, Yunus started giving them loans of $27 out of his own pocket. The women used the loans to purchase supplies such as bamboo to build stools to sell. These microloans changed their lives, Yunus said, enabling them to provide for themselves and their families.

In 1983, after exhausting efforts to convince conventional banks to work with poor clients, Yunus established Grameen Bank to provide microloans. The bank later expanded throughout Bangladesh and now operates worldwide. Grameen, which means “village,” is run by women stakeholders and sees a repayment rate of 99 percent. In all, it has disbursed collateral-free loans of $24 billion to 9 million borrowers worldwide, including clients of 11 U.S. branches.

“Financial services to poor people is like oxygen,” said Yunus, whose moniker Banker to the Poor serves as the title of his first book. “The moment you connect [people] with financial services, they become alive; they become active; they become productive; they become creative.”

Just as there is nothing physically wrong with a person who is cut off from oxygen, Yunus said, there is nothing wrong with the poor. But there is something wrong with a system that creates poverty and provides no way out.

“Fix the system,” he admonished.

The growing inequality of a world in which 1 percent of the population owns 99 percent of the wealth is “a mockery of a system,” Yunus said. “It’s a ticking time bomb. It will explode [at] any time unless we do something about it.”

THE GREATEST THREAT TO HUMANITY

Throughout her address, “Faith vs. Fury: The Moral, Legal and Rational Argument to End the Nuclear Threat for Good,” Beatrice Fihn frequently invoked the words of Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., whose ardent support for denuclearization inspired the founding of the Kroc Institute in 1986.

“He was a resolute defender of humanity in the face of nuclear destruction through his last days with us,” Fihn said.

ICAN is similarly focused. Based in Geneva, the campaign brings together non-governmental organizations from 100 countries to advance the United Nations’ 2017 nuclear weapon ban treaty. In awarding the peace prize, the Nobel committee praised ICAN’s efforts “to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons.”

Fihn explained the paradox of people accepting the idea of nuclear weapons even though they could end humanity as we know it.

“We just assumed that somebody was in charge and that there were cooler heads and experts dismantling this threat,” she said. Fihn quoted Martin Luther King Jr., who said that we put the nuclear threat out of our minds because it is so overwhelming and painful that denial is natural.

But changes in the past two years compel us to pay attention, she added.

“The reasonable voices we envisioned controlling our nuclear missiles turned into men shouting on Twitter about the size of their nuclear buttons,” she said. “We could no longer ignore these objects of global destruction.”

Further, it is not reasonable to expect to maintain and expand nuclear weapons without using them.

“We will not live with nuclear weapons forever without them being used with catastrophic consequences,” Fihn explained. “A mathematician will tell you the likelihood of nuclear weapons being used at any given time is greater than zero, and that risk fluctuates.

“Right now, the likelihood is definitely higher than it was last year thanks to a growing threat of conflict.”

Fihn urged audience members to learn more about nuclear disarmament efforts by subscribing to ICAN’s publications, researching whether their financial institutions invest in nuclear weapons, voting, and seeking ways to register their views with policy makers.

“[Change] doesn’t come from the current people in power,” she said. “It always comes from people who changed the context in which politicians operate.”

— Christine Cox

To learn more about Keough School events, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.